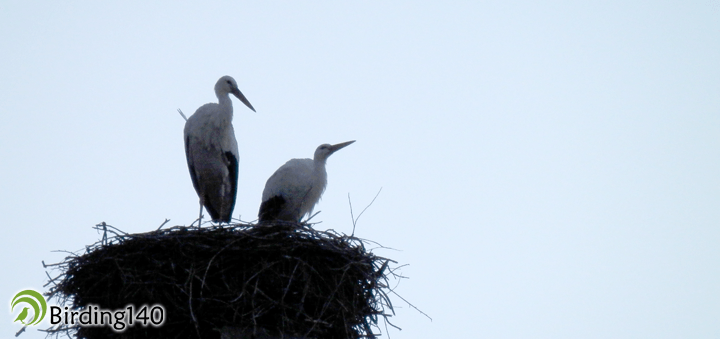

The answer is yes, but with some nuances. There are more than 8 600 species and 92 % of them are monogamous. Among the most loyal species we can find storks, geese and swans, which go as far as being together night and day during the whole year. We can even see them together during the migrations, when they travel for thousands of kilometres.

In the monogamous species, both the male and the female take care of their young. Courting is very important, because it creates a bond between the couple. The longer the bond is, the less possibilities there are for the female to mate with other male. Moreover, this bond guarantees that the male doesn’t have time or desire to start a new relationship. All in all, we understand the existence of jealous females who eject other females from their territories, and that the males watch their fertile partners. In some species, the courtship rituals regulate the sexual pattern of the couple. We can see an example of this in the female Common Wood Pigeon, which doesn’t reach sexual maturity until courted by a male.

Monogamy depends on many factors. If a species requires a lot of attention from their parents, it has more possibilities of being monogamous, like albatross, petrels and shearwaters. Another factor is food scarcity: in this situation, joining forces is a good strategy to support the young. A research on the Winter Wren was carried out to prove this. In the island of Saint Kilda, where food is scarce, this species is monogamous and both parents feed the young; whereas in London, where there are more possibilities of filling the stomach, the reverse is the case. Another factor that benefits monogamy is nesting colonies. In those, the males fiercely watch the females during the fertile period. An example of this is the Sand Martin. According to a study carried out by the researchers of the Department of Zoology of the Oxford University, in which 276 bird species where analysed, the conclusion is that the females who are more loyal to their partners receive help from the group to raise their nestlings, whereas those who are more promiscuous don’t.

There are more “infidelities” when territories with several males are very close to each other, because it favours the possibility of mating with several specimens. These cases are very common among Red Junglefowls.

There is also “ambiguity” in some bird species: for example, the Indigo Bunting can jump from monogamy to polygamy. Apparently, when there is plenty of food, up to two females can come together with a male, and get back to monogamy in times of scarcity.

The real master of couple deceit is the male European Pied Flycatcher, who behaves as if not “compromised” when being in contact with a single female. To avoid this kind of behaviour, some females, like the female tit, dedicate many hours to watch their partners, and they are ruthless when ejecting other females out of their territory. They also undertake a lot of copulation: they dampen the strength of the male so he is not able to mate with other females; plus, it increases their chances of fertility.

We can see a downside in some ducks. We are talking about the few birds that have an actual penis, so they can force the females to mate. Raping is very frequent among species like the Mallard.

All relationship has its ups and downs, and sometimes it leads to divorce. There are two species of migratory swans in Great Britain: the Bewick’s Swan, which flies long distances from the Russian tundra, and the Whooper Swan, which makes short migrations. The biggest divorce rate is among the Whooper Swan, because the couples are not in contact for as long as the Bewick’s Swan couples and their bond is weaker.

As you have seen, bird’s and human’s couple behaviour are not so different.