The lake looks impressive and quiet. A light breeze caresses the reed bed. Two V-shaped shadows skim the reeds with a dancing show in the air after being woken from their lethargy by the rays of a shining sunrise. Hovering in the sky, the couple of Western Marsh Harriers observes the life of the water sheet in search for a prey.

Marsh Harrier (Circus aeruginosus) | Autor: Stefan Berndtsson · Creative Commons: Attribution 2.0 Generic

In the grain fields on the other side of the wetland, the Montagu’s Harrier protects a secret hidden under its greyish plumage in the sun. The eggs maintain the proper temperature under the female, awaiting to start the path of life before the harvester is put into operation.

Montagu’s Harrier (Circus pygargus) | Autor: Michele Lamberti · Creative Commons: Attribution 2.0 Generic

In a boundary at the end of the path that separates us from the wheat field, we find the impressive Hen Harrier taking a breath after a skirmish with a vole which now lies lifeless under the powerful claws of the bird.

At the back, over a wasteland, a Pallid Harrier crops its silhouette as if playing with the heat currents formed at ground height. Its slow elegant flight invokes a feeling of serenity and warmth. During this short tour, we have just met the four harriers that live in Europe.

We will now try to learn a bit more about these birds of the genus Circus, which comes from the Greek kirkos and means “hawk which flies in circles”. This kind of predators don’t need ledges or forest masses. The four harriers that wander around Europe are associated to grain fields, reed beds and moorlands.

The Western Marsh Harrier, the Montagu’s Harrier and the Hen Harrier are fairly common, while the Pallid Harrier is rarer, except in Eastern Europe. In order to differentiate them from other birds of prey, we have to look at their long tails and wings: the latter form a shallow V as they glide exploring the ground.

Where do harriers live and how do they hunt?

The typical habitats where we can found them overlap, especially in winter and during the migration. But we should look for the Western Marsh Harrier among the reed beds in the wet areas. The Montagu’s Harrier can be found in the grain fields and the pastures surrounding the wetlands. The Hen Harrier is found in moorlands, pastures and crop fields, although they are seen in crops around the wetlands during the breeding season. Lastly, we can find the Pallid Harrier in more open areas (steppes and pseudo steppes).

There is a simple but indicative rule to help us differentiate between a Montagu’s and a Northern Harrier. If we are in the Mediterranean basin during the summer, we are more likely to see a Montagu’s Harrier. Meanwhile during winter in the north of Europe, it will quite surely be a Northern Harrier.

Female Marsh Harrier (Circus aeruginosus) | Autor: Michele Lamberti · Creative Commons: Attribution 2.0 Generic

Harriers are birds of prey which slide silently like shadows at a low height from the ground. Their fast twists before they suddenly fall over the preys hidden among the plants and the grain are possible thanks to their long wings and their powerful tail. All of them will take a short and vertical swoop down over their preys. The Western Marsh Harrier stands out because it keeps its captured prey under the water until it drowns.

Its long tarsus and short paws have powerful and sharp claws that are used as a harpoon against the preys before they can run away. The Western Marsh Harrier flies low over swampy areas before suddenly swooping down over its prey, and it usually turns around during the process. They frequently prospect around the borderlines too, and their low flight doesn’t follow a specific pattern. The Montagu’s Harrier flies over open areas during the breeding season and follows a regular rhythm. Meanwhile, the Pallid Harrier patrols in open areas, in a low but regular flight.

How to distinguish the different harrier species

The Western Marsh Harrier has a bigger size and a wider tail. It flies with a characteristic V-soaring, alternated with slow flaps. It doesn’t have any white colour in the rump (part of the body immediately superior to the tail of a bird). The male is brown and dark in the back, while the female stands out due to her clear throat, head and shoulders over a chocolate-brown plumage. This can be contrasted by analysing its Latin surname, aeruginosus, which means “covered in oxide”. The young bird is dark brown without contrasts.

Marsh Harrier (Circus aeruginosus) | Autor: Biodiversity Heritage Library · Creative Commons: Attribution 2.0 Generic

The Northern Harrier is more robust than the Montagu’s Harrier, although the male doesn’t have the black wing tags of the Montagu’s. However, its Latin surname, cyaneus, means “dark blue”, which alludes to the colour of its plumage. The females are reddish-brown with barred tails and have a quite speckled plumage.

Hen Harrier (Circus cyaneus) | Autor: Biodiversity Heritage Library · Creative Commons: Attribution 2.0 Generic

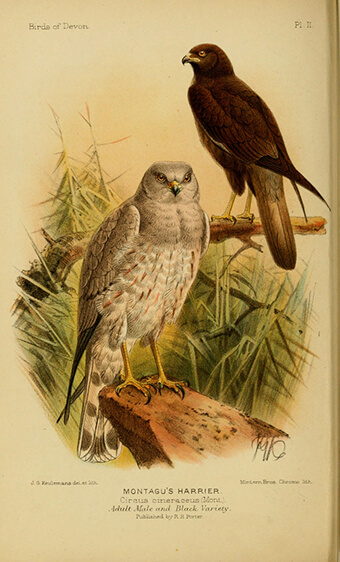

The Montagu’s Harrier is the most slender and stands out due to its leaden grey colour, although we must say that there are melanic specimens which are totally black. It also has a smaller size than the Hen Harrier. Its Latin surname, pygargus, means “shiny rump”. Female and young specimens stand out due to their barred tails and their reddish colour, although the latter don’t have bars in the tail or white colour in the rump.

Montagus Harrier (Circus pygargus) | Autor: Biodiversity Heritage Library · Creative Commons: Attribution 2.0 Generic

The Pallid Harrier is the smallest of all. It can be differentiated from the rest by its grey rump and its white chest and cheeks seen on flight. The females and the young specimens can be confused with Montagu’s Harriers, but can be distinguished by their white collar and a characteristic dark patch in their ears.

Pallid Harrier (Circus macrourus) | Autor: Biodiversity Heritage Library · Creative Commons: Attribution 2.0 Generic

How do harriers feed?

The Western Marsh Harrier especially eats small birds, but also reptiles, amphibious and fish, while the Montagu’s, Hen and Pallid Harriers feed on rodents and small birds to a large extent, for which they use peculiar hunting techniques. All of them, but specially the Montagu’s Harrier, undertake prospection flights at a low height over the ground, which they interrupt with short and sudden plummets.

Both the Western Marsh Harrier and the Hen Harrier perform interesting techniques in combination with other predatory species. The first one captures most of its preys over the waters where they live, but if it shares the territory with the Peregrine Falcon, a kind of symbiosis and mutual help occurs in order to earn their food.

Water birds remain in the water, in the presence of the Peregrine Falcon, and the Western Marsh Harrier takes advantage of it. After the capture, the commotion and the subsequent frightening are used by the Peregrine Falcon in order to catch its prey.

On the other hand, the Hen Harrier benefits on the technique used by the Merlin to hunt insects. It places itself under the Merlin, flying at a lower height, and takes advantage of the disturbance provoked by the small predatory among other birds.

The nuptial flight of the harrier

The nuptial flights and stops of the harriers are especially noteworthy. When the male Western Marsh Harrier catches sight of the female, he swoops down over her. She revolts with several ringlets in the air until she turns around and opposes her claws to the constant swooping down of the male.

The nuptial flight of the Montagu’s Harrier has two phases. During the first one, both male and female carry out synchronized flights, until the male separates and rises to end up plummeting over the female.

During the second phase, the male calls the female with shrieks from the ground and chases her when she arrives. After the male swoops down, the female turns around until they join their claws, opposing them for an instant. The rest of the species have similar behaviours, but they are not as clearly defined. As a curiosity we must say that, despite showing such an elaborate and spectacular courting, polygamy is quite common among harriers.

The nests of the harrier

The last one going into heat and building the nest is the Montagu’s Harrier, around middle May. On the contrary, the rest of the species start the heat at the end of April. The nests have platforms of smashed grass on a two meter radio over the ground, in order to facilitate the exit and arrival to the nest. It is fair to mention the case of the Western Marsh Harrier, which can make real floating platforms out of rush or reed.

Moreover, all harrier males defend the nest in a very hostile manner, even attacking birds of larger size, like vultures and Golden Eagles. Incubation is carried out during June, and extends until almost the end of July in the case of the Montagu’s Harrier.

They lay from three to six eggs of a bluish-white colour, with specks in the case of the Pallid Harrier. The largest eggs are the Western Marsh Harrier’s. As a curious fact, we would like to say that the incubation takes about forty days, and there can be small breeding groups.

The Northern and Pallid Harrier chicks stay in the nest until late July. In the case of the Western Marsh Harrier, they don’t abandon the nest until mid-August and, in the case of the Montagu’s Harrier, until almost the end of August.

The laying, with a two-day interval between egg and egg, causes inequalities among the chicks. For this reason, the older brothers fly up to two weeks before the youngest ones. The chicks complete their development on the ground and show an aggressive behaviour towards intruders. However, when there is a great danger, they can scatter or remain quiet as a defence mechanism.

The Western Marsh Harrier gatherings in the Castilian meseta (Spain) after the growth of the chicks are worth pointing out. They make communal roosts in the marsh vegetation, taking advantage of the demographic explosion of voles for their nourishment.

Where to see harriers in Europe

We have to bear in mind that all of them spend the winter in Sub-Saharan Africa. Although during their wintering, large groups of Hen and Western Marsh Harriers join the population located in the Iberian Peninsula throughout the year.

´

In Spain stand out the lagoon complexes surrounded by crops, like the lakes of Villafáfila and La Nava in the northern side and the National Parks of Cabañeros and Tablas de Daimiel in the south. In these four places we can catch sight of the four harrier species almost all-year round, but especially during the summer season. The presence of the Pallid Harrier is very rare.

In the rest of Europe we can find Montagu’s, Western Marsh and Pallid Harriers in Faslterbo (Sweden) during autumn, and in the Straif of Messina (Italy) during spring, as well as in Norfolk (England) in the summer season. Meanwhile, the Hen Harrier only bestows in the Outer Hebride Isles in Scotland. As an anecdote, the Pied Harrier, which comes from Asia, can accidentally be found in Ussuriland (Russia).

The threats faced by European harriers

The Western Marsh Harrier is the most threatened species. In general the harrier populations in Europe are more or less stable, although they have shown a significant decrease during the last years. We have to bear in mind that the tendency could be very negative in a future without specific protective measures.

In order to prevent the decline of their populations, it is crucial to raise awareness among the farmers and the rural environment. It is important to respect the nests located in the crops, and to make sure that the benefits provided by these birds of prey are known in rural areas, as they are a great ally of farmers in the control of rodent plagues that decimate the harvest.

The campaigns to save the chicks and the delay in the harvest are very important, especially for the Montagu’s Harrier due to its dependence on cereal crops. The Western Marsh Harrier is more affected by the pollution and destruction of wet areas. All of them are victims of hunting and of the plundering of their nests. It is worth mentioning the situation of the Hen Harrier in Scotland, where the preys are decreasing in their breeding areas due to intensive hunting.

Montagu’s Harrier (Circus pygargus) | Autor: Marina Sanz Biendicho · Creative Commons: Attribution 2.0 Generic

In the Iberian Peninsula, the situation of the Montagu’s Harrier is starting to be worrisome. In Extremadura and Catalonia there are captivity breeding programs, and some regions carry out chick rescue campaigns. However, the species seems to have entered a steep slope.

The GIA (Grupo Ibérico de Aguiluchos or Iberian Harrier Group), constituted by GREFA, AMUS and ANSER, among other associations, was created to protect these birds in Spain and Portugal. Last November the GIA held the XIII Iberian Harrier Congress, where some measures were proposed in order to try to stop the decline of the Montagu’s Harrier, such as the creation of a new census or a greater implication of the public institutions. From Birding140 we are going to cooperate with GIA taking care of the awareness and image campaign. All together, we hope we can improve the situation of the harriers.

Only from education and respect can we keep enjoying the low height V-winged silhouette of these predators. For this reason, we must be aware of the work and benefits that harriers bring to our fields. With a little effort and a change in the agricultural customs, future generations will surely be able to keep enjoying their presence. With these lines, we hope to have contributed to help you know our European harriers a bit better.