The evening light was vanishing. In the autumn atmosphere, the cold wind interrupted the distant trumpeting sound while making whirlpools in the lake. After a short silence, the wind filled with small winged Vs approaching the water in order to rest after a whole day seeking out sustenance. The outstretched necks and the long wings were gradually becoming clearer, with those characteristic black flight feathers. The sun was fading out behind the horizon, and the large group of cranes arrived to the lake ready to spend the cold night.

The previous image has fascinated people from all cultures since ancient times. Cranes have been on Earth for 55 million years. In fact, they have been represented in cave paintings, and it is believed that humans imitated their dance around 7000 B.C. in Japan. We can understand this if we know that cranes are able to use over 90 gestures and sounds.

They have also left a trace in literature: Homer talked about their song in the Iliad, Plutarch described Theseus as a crane when he defeated the Minotaur, and according to Greek mythology, the god Hermes invented writing watching the forms the cranes made in the sky. It is surprising to know that words like “geranium” or “pedigree” are an indirect influence of these birds in the language. The first one means “crane” in Greek, because this plant’s seeds look similar to a crane’s head; the second one comes from the French expression pied de grue, due to the similarity of the family tree and this bird’s leg.

In Europe we can only observe two of the fifteen crane species that exist in the world. The normal scenario is finding a Common Crane (Grus grus). But almost anecdotally appears the Demoiselle Crane (Grus virgo), the smallest crane in the world. It seems like most of the quotes correspond to releases or escapes of zoological collections, although it is known that it was introduced in France from Russia in the 18th century by order of Marie Antoinette, and it got the surname of “demoiselle”. Anyway, the best option to see this kind of cranes in Europe is getting close to Cyprus, where we can enjoy their migratory flight from March to April.

The Common Crane breeds in wetlands in Germany, Estonia, Finland, Norway, Poland, Russia and Sweden. But at the end of the summer, this dames of the cold notice that there are less hours of light and they start the most fascinating stage of their lives. This migration gathers thousands of followers that say goodbye or welcome these birds in Sweden, the islands of the Baltic Sea and Germany. Their big size, combined with their behaviour, makes crane roosts a really attractive phenomenon.

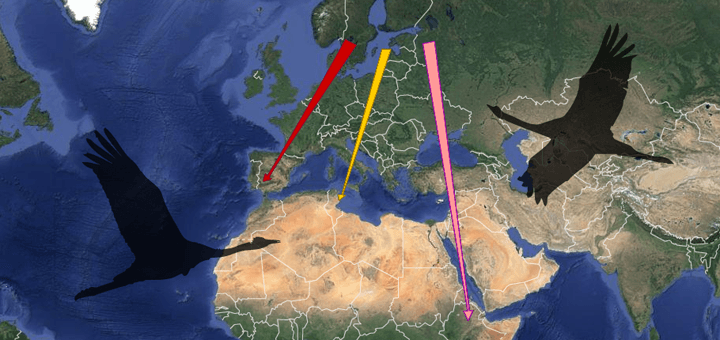

But let’s see how they do it. Cranes use three migratory routes. The western route, used by about 130.000 birds, leads them to spend the winter in Spain, Portugal and Morocco. The central or Baltic route, where approximately 140 000 cranes try to reach Africa from Poland crossing Serbia and Italy. Lastly, the eastern route, used by an undetermined number of cranes, departs from Estonia and Russia, crosses Turkey and Egypt and arrives to Ethiopia.

But let’s follow one of these cranes during its adventure, keeping it company on the western route. We will go over 4000 km to arrive to our winter quarters. To do so, we will reach up to 9000 metres altitude. This way we will cross Europe in a fascinating trip.

For our route, we will depart from the usual concentration places. The most important ones are the lake Hornborga (Sweden), the Öland island (Baltic Sea) and Rügen (Germany). From here, we will cross Germany and arrive almost breathless to the first resting spot. The Champagne Lake (France) will help us recover strength for the next stage. But the hardest is still to come.

The mountain range of the Pyrenees separates us from our destination. The strength is starting to diminish and we will stop again in Capiteux before crossing the mountain range. Now comes the litmus test: reaching the Iberian Peninsula is a matter of time. The weakest have stopped along the way. They are not likely to join us on our trip back. The winter cold will do the rest.

Already in Spain, the lake of Gallocanta looks like an oasis in the middle of nowhere. Its strategic location and its dimensions channel each year no less than from 20 000 to 60 000 specimens. From here, cranes will distribute around the Peninsula. A 16 % will stay in Aragon. About 18 % will arrive to Castile-La Mancha, and about 10 % to Andalusia.

But Extremadura is without doubt the community where most specimens arrive, with a 53 %. However, 70 % of the cranes in Western Europe come to Spain each year to spend the winter incessantly from October until early December. On the trip back to the breeding areas, they follow a more channelled route on the east of the Iberian Peninsula.

In order to watch this extraordinary show, we recommend to come to the roosts with optical supplies well in advance, at sunrise or sunset. This way we won’t interfere with the cranes’ way out or into the roost. We should bear in mind that a single person or vehicle arriving late can alter the way in or out from the roost, spoiling the vision for the other observers.

In Spain, during the autumn migration (from October to December), the spectacular nature of the entrance of the cranes to the roost is bigger than during the spring crossover (from March to April), because the crane concentrations are larger in number. Moreover, we should bear in mind that they feed during the day and make their entrance in a few minutes before sunset.

Many will ask themselves how you can hear these Gruiformes long before seeing them. The answer is that their trumpeting sound can be heard from a distance of 5 km. Their large trachea is linked to the breastbone by bony plates, and wraps in the chest forming a box of natural resonance.

Moreover, they increase the latitude in their trips when they cross towns or cities. That, combined with the fact that they sometimes fly over the clouds, means that we sometimes can hear them but not see them. Still, it is easy to observe small familiar flocks crossing large European cities like Paris or Madrid.

The migration of the cranes and its concentrations in winter quarters are an amazing phenomenon based in ecological balance. This is way they can be affected by human activities, in such a way that the extinction of the pastures and the agricultural changes, as well as direct disturbances, can end up damaging this balance. They can also put at risk having cranes in our fields.

To avoid this we need to work for their conservation by carrying out information campaigns in the towns of the regions concerned. As well as the stimulation of the tourism sector focused on these birds in the mentioned regions. To achieve this, we should have a strategic plan that gives as a result an ethical and responsible ornithological tourism. Only this way can we make sure that future generations see these birds in their characteristic V-shaped flight and enjoy their trumpeting sounds and their dances.

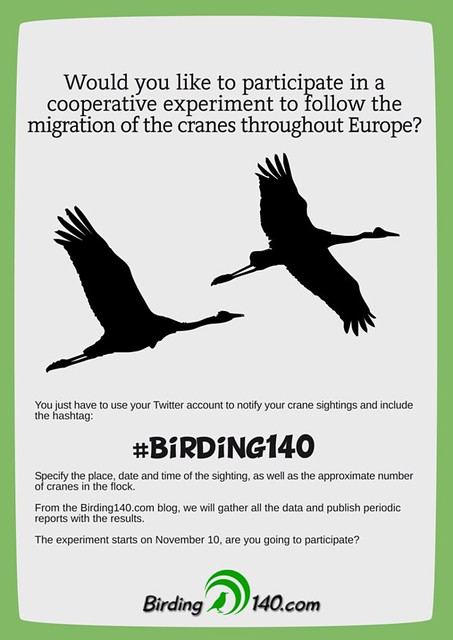

From Birding140 we are supporting the cranes in their long trip. We have a collaborative experiment going on where everyone can participate, from the north to the south of Europe. If you see a flock of cranes, let us know through Twitter with the hashtag #Birding 140 and specify the place, date and time of the sighting, as well as the approximate number of cranes in the flock. We will gather all the information and write periodical summaries with the information obtained from the migratory trip of the cranes throughout Europe. Do you want to participate?